Greetings from a Sydney heatwave – It’s over 40 degrees again!

I think I’ve been involved in enough Guided Inquiries now to know ten easy ways to make the unit fail. Here they are…Don’t, on any account,do any of these!

This might seem a self-evident thing to say, that teachers need time to read about and apply Guided Inquiry to their own learning, to understand and how it might work with students. Time, however, is the missing element in busy schools, with teachers barely keeping afloat in the sea of classes, marking, and accountability confronting them. In Australia, the content-heavy curriculum is another challenge for finding time for professional development. It is of the utmost importance that at least the teaching team conducting the Guided Inquiry learns about the theory and practice of Guided Inquiry. The second edition of Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century, is especially useful in providing this professional development. The Australian Guided Inquiry Community also provides Australian examples and scaffolding for those seeking to gain an overall understanding of what’s involved in a GI (with an Aussie flavour!) The provision of time for teacher professional development is a huge challenge in busy schools.

Collaboration between the members of the teaching team is essential throughout the GI, from design, to scheduling, to teaching, to responding to students individually or in groups; to discussing student progress and sharing the load of responding to students in work sessions; to assessing the process and product of students; to reflecting together in a culmination conversation on what worked and what didn’t, and how to improve the running of the unit next time. This is stating the obvious! But achieving such collaboration is difficult in a busy school, and it is all too easy for one part of the teaching team to run away with the design of the unit. This reduces the ownership of the GI, by either having it a teacher-created unit, without the expertise of the teacher librarian; or the teacher librarian rushing ahead and creating the unit, without the ownership of the teacher(s).

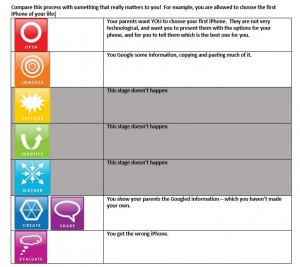

Students need to be introduced to the GI process in a way they can relate to, such as The Research River, or something like the following:

Sorry, these are a bit little!

Sorry, these are a bit little!Students need to have posters of the GI process in their work area in the library and classroom, and to have members of the teaching team bring it to their attention throughout the GI.

4. Don’t cover all the stages of the GI process.

Listen to students such as Eternity (pseudonym) in the 2015 research carried out by Dr. Kasey Garrison and me, who said:

No, I like to do things in a different order to how they suggested it. I liked the end, some of the stages, and the Create and Share part, I found that really fun but the other parts…(No, I didn’t like them).

As Eternity suggests, the GI could leave out all the stages in the middle and go from Open to Immerse to Explore to Create and Share. Which is pretty much the same as Google, Copy and Paste, and Plagiarise and Present!

DO allow students to reflect on the GI process throughout the unit – this reflection from Freddo at the end of two GI’s in last year’s research is engaging! She reflected that the stages of GI were “like stickers in your brain.” (In Australia, “stickers” mean post-it notes).

5. Don’t resource it properly

The types of resources students need at different stages of the GI process make resourcing the unit a highly specialised task for the TL to carry out, with the assistance of the teacher(s). Overview sources are needed at the beginning of a GI, so that students can get an idea of the scope of the topic(s) they are choosing between, or have been allocated (in a single topic GI). It’s wise to stay away from Google at this stage, as the level of detail it provides is often confusing at Explore. Youtube and Clickview videos are excellent at Explore. After identify, where students have created their inquiry question, the need for pertinent resources to each individual question involves the TL in another search for resources, and in teaching students how to find their own on online data bases and elsewhere. Google is good at this stage, with careful searching. There can be a difficulty in the Gather phase of sources being too hard for students to read, and use of scaffolding on how to read interrogate sources, such as those found in A Guided Inquiry approach to teaching the humanities project (Schmidt, et al, 2015) will be useful.

6. Don’t allow enough time to carry it out

The demands of the highly content driven nature of the Australian Curriculum (while it still abounds in information skills and the General Capabilities) is a challenge for GI, because there is little time to spend on topics outside the curriculum. This means that GIs mostly focus on single curriculum topics which are part of the syllabus, apart from the occasional open-ended investigation that occurs in senior History and Geography. It also means that time is precious and allocating the time needed to cover a GI is hard to organise. The way we’ve got around that is to regard the class as an inquiry community, as suggested by Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, (2012), which is finding out about, and sharing knowledge of aspects of the topic, so that the GI covers the curriculum topic by inquiry rather than teacher instruction.

7. Don’t allow students to choose their own areas of interest

It is difficult for teachers to let go of their knowledge of individual students and not to steer them away from an aspect of the topic they know may be challenging for them, or too easy for them, even though they express interest in it. This is of course, a critical aspect of GI, student choice and interest being its driving force towards success.

8. Don’t allow students to create their own inquiry question

Students need scaffolding to understand what constitutes a higher order question, and the Question Focus Formulation technique (Rothstein and Santana,2011) works very well. Teachers and TLs need to restrain themselves from tinkering with student questions, as it is very easy for students to lose ownership of their question, and thereby lose interest.

9. Don’t encourage students to reflect throughout the process: Allow them do it all at the end!

It seems that Holly Bell from our CSU 2015 research, (which is still being analysed) was able to leave all her reflecting till the end, and naturally didn’t enjoy it!

Well, to be honest, I actually really, really, don’t like reflections, I just find it so annoying, I have done all of this work and then it is… how do I know three weeks ago what was I feeling??

If students know why they are reflecting – to allow teachers and TL to know of their progress, what they are feeling, what difficulties they are having; as well as becoming more conscious of their own learning process; it becomes an integral part of the process. DEFINITELY, not to be left till the end!

Reflections based on the SLIM Toolkit from Centre for International Scholarship in School Libraries (CISSL) are simple and direct, and also form data for evidence-based practice.

10. Don’t assess it in innovative, formative and summative ways.

Assessment in GI needs to be formative as well as summative. It should involve students assessing their own and their peers’ work, reflecting on content and process, and celebrating and showcasing learning. In GIs I’ve been involved in, there are marking rubrics for product and for process, and the “value” of the project in terms of grades is perceived by students as equally comprising of their product and their process. Here are two examples of the kinds of rubrics we have used at my school in Sydney:

We often used wikis as the working space of GI, which allowed for continuous feedback to individual students, as well as the vehicle for students to contribute all the parts of their GI. The culmination conversation is a recommended GI technique for the teaching team to have a structured conversation about successes and shortcomings of the unit, the progress of individual students and further interventions needed. In my school in Sydney, we introduced a culmination conversation for students, a round-table discussion, where each student is given a higher order question relating to the topic they investigated, (not the same as their inquiry question), 5 minutes to think about it, and then 3 minutes to talk about it in front of their peers. It is possibly the most rewarding thing in a GI, to see the passion with which students apply their thinking and speak about their own topic area with ownership, understanding and divergent thinking. It was very rewarding hearing students at the end of the unit on the Holocaust, in which they worked in inquiry circles – Bystanders, Upstanders, Perpetrators and Victims, respond to questions such as: Why do some people stand by during times of injustice while others try to do something to stop or prevent injustice? It was clear that The Holocaust GI had engendered deep interest and commitment.

As you see, there are at least ten ways to derail a perfectly good Guided Inquiry! Nobody would ever dream of doing any one of these!

Lee

I promised myself that I would keep up with all the posts on this site, but have failed miserably… I have to say, though, that, Lee, you put a giant smile on my face with today’s post. You’ve touched on a number of struggles that we have had as people “kinda” get it and put together something that has a similarity to a GI unit but fails in significant ways. I still stand by statement a few weeks ago that some elements of a GI unit will improve a traditional research assignment, but when a GI unit truly hits the mark, it is magic and we should always be striving to do it properly. Thanks for the informative and humorous posts!